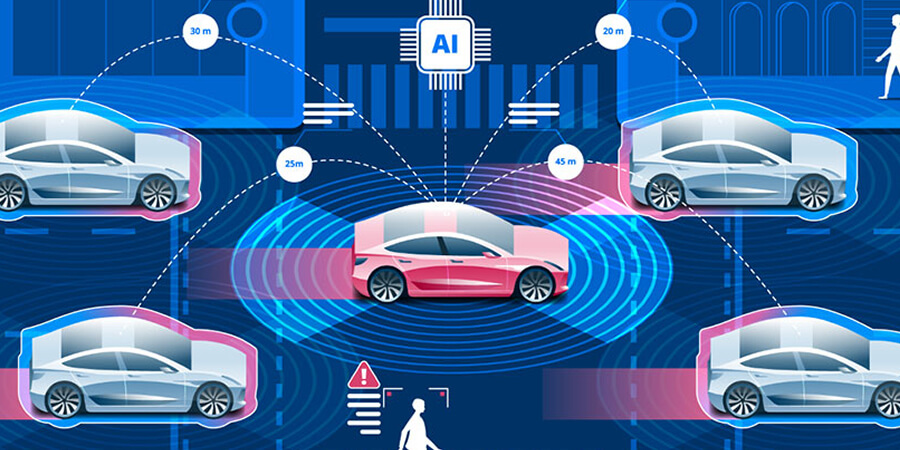

Autonomous and connected cars have already been trialed on the streets of many countries over the past half-decade. Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and the internet of things (IoT) have made way for the surge in the trialing and adoption of autonomous vehicles. It has been forecasted that by 2021, over 380 million connected cars will take to the streets. In fact, after the smartphone and the tablet, the connected car has been deemed as one of the most rapid-growing technological device.

Alex Khizhniak, director of Technical Evangelism at IT services provider Altros, stated, “Being connected to other cars on the road will eventually make driving much safer. Combined with predictive analysis, smart systems could substitute for a driver in case of emergency. Although these technologies are still developing - and some legislations should also be introduced- the future looks promising for self-driving and intelligent driving assistants.”

While many have been vocal about their concerns regarding the regulation of autonomous or connected cars, there are many advantages that must be considered before delving into the risks.

One of the many key benefits of connected cars is that they could contribute to safer traffic patterns in cities with congestion issues as a consequence of rapid urbanization.

In theory, connected cars ensure safety by providing the driver with the ability to reach their destination in the quickest and most cost-effective way possible. This is achieved by communicating with traffic signals and road infrastructure to, for instance, ensure the drivers and passengers of the respective vehicle slow down before the signal turns red. It has actually been forecasted that the amount of car accidents is expected to subside once connected and autonomous vehicles are more widely adopted.

Drivers would be alerted with regular reports on potentially dangerous roads and weather conditions based on big data analytics, another emerging technology with boundless potential which has reshaped every industry.

Many major players in the automotive industry have gone so far as to speculate that self-driving cars will eventually be an even safer option than the connected car despite not having a driver behind the wheel. This statement, albeit debatable, holds some truth. Driverless cars create a more aware driving environment as they have the ability to recognize risks, respond to them accordingly and to also recognize other driverless cars on the road.

Risks and ethico-legal issues

Indeed, connected cars offer a wide array of advantages but they also come with their disadvantages and risks. Understanding these risks and creating a regulatory framework to ensure greater safety are key.

While connected vehicles collect a sheer amount of data which could be used to improve designs and give urban planners and traffic managers greater insight into how to better utilize their resources and plan more effective driving experiences for the city’s residents, tremendous risks are imposed.

Data in this situation can be seen as a double-edged sword in the way that it can provide incredible insight and make way for greater improvements, it could in some ways undermine the right to an individual’s privacy. Many users would not particularly agree with the prospect of their data being extracted from their cars could act as collection points for car manufacturers and internet providers to improve their marketing strategies.

Another risk in this situation would be product liability. Manufacturers of these vehicles need to pay a great deal of attention to the potential product liability risk involved in the event of individuals or properties being damaged by or in circumstances surrounding connected or autonomous cars.

Many are of the belief that if this ever happens to be the case, the liability would fall into the hands of the technology itself as opposed to the driver, weather conditions of road infrastructure, hence limiting defenses. In such a situation, if a plaintiff were to pursue a company, they would try to gauge an understanding of the company’s AI capabilities such as what guides the AI and how the vehicle has been programmed to reach in certain situations.

As more autonomous vehicles take to the streets, the responsibility of accidents will shift away from the driver and onto the vehicle itself in terms of design and manufacturing. This will probably cause more companies to be liable for accidents that take place and the complexity of these cases will undoubtedly increase. An anticipated issue which will stem from this is the assessment of whether the software or the hardware of the vehicle caused the accident which many companies will find particularly difficult as they will have to refer back to the entire supply chain involved, many components of which will lack access to proprietary source code.

In the case of semi-autonomous vehicles, the key to understanding the legal complexities lies in the notion of handover/takeover transitions which refers to the point at which the control is passed onto the vehicle itself by the driver and vice versa. Liability regimes in this scenario are a great deal more fluid.

The question of ethics is key when it comes to matters of consent and autonomy in the face of an accident, as it essentially underpins the very foundation of the legal measures which lead up to the transition phase.

It is a fact that relatively new technologies could bring about unprecedented challenges. The purpose of advanced driving aid systems is to diminish the risks associated with driving such as human error, among others. These systems use intelligent sensors to mitigate the risks by either providing the human driver with additional information or by taking temporary control of a specific aspect of the vehicle’s operation. These offer a wide range of safety benefits but it brings with it some challenges. A study found that some elements of advanced driving aid systems technology which could come to play in the event of a collision or potential one, would bring about some ethical challenges. The researchers, Maurer et al. stated in their paper, “In the event of the car sensing a threat and being able to determine a strategy to avoid it, it is ethically obliged to intervene.”

“The most important characteristic of dynamic systems is that the system be contextual. That is, it needs context and contextual information in order to be safe and accurate in its behaviors and responses to dynamically changing conditions. An enormously important source of that contextual information for vehicles on the road is from other vehicles, specifically from connected vehicles and connected sensors. Those connections deliver early warnings and other critical data for safe maneuvering in a dynamic environment. Therefore, the connected car not only provides infotainment to its passengers, but it also provides actionable information, safety recommendations, and contextual insights for the benefit of all drivers on the road,” Kirk Borne, Principal Data Scientist at Booz Allen.

It is of the essence to consider that, for the public to accept and adopt self-driving cars into their lives, they must trust the technology and the moral framework that underpins their functionality. But this can be quite tricky as not all morals are created equal and moral implications can be very different depending on culture.

Some weighty hypothetical moral questions or scenarios which can be considered in the case of connected or autonomous cars would be: Should the lives of pets be preserved over humans? Women over men? Pedestrians over passengers? Young people over the elderly? Should those of higher social status be saved such as doctors or business men? What about individuals who are more physically fit? While these questions may be hypothetical, they are all real life scenarios and they represent decisions that the autonomous car would have to take.

Perhaps designing emotionally intelligent AI or an ‘artificial conscience’ which could be altered to adapt to any given society’s moral belief system could be the answer.

Regulation

This brings to question: Who decides the moral dilemma of what algorithms decide?

Many governments across the world have already started discourse around the legislation for this technology.

Eric Tanenblatt, global chair of public policy and regulation at global law firm, Dentons, commented on the matter and stated, “Government regulation is definitely needed… We’re talking about a paradigm shift in the automotive industry. And there are so many areas that are touched by autonomous vehicles.”

“There’s the whole angle of safety; there’s the whole angle of insurance and data privacy. There’s a number of ethical issues and it’s something that is new,” he added.

Indeed, because connected and autonomous vehicles are so new, different countries are at different stages of the regulatory process. However, it is instrumental that all governments involved in devising a regulatory framework for this take the time to address as many issues as possible from the get-go.

UK

The UK has been regarded as one of the countries that has been at the forefront of introducing and assessing regulation in this area. The country’s government has set up a new department, the Center for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles and has begun testing schemes in several cities, some of which include Coventry and London and have recently revised and updated the Code of Practice for Automated Vehicle Trialing which will essentially provide some much-needed clarity regarding the expectations of organizations which are planning to trial these vehicles.

The UK’s Automated and Electric Vehicles (AEV) Act 2018 states that the owners of these vehicles would only be liable in special circumstances, one of which is when the driverless car itself is not insured. However, depending on the situation, the insurer may pursue some claims against the manufacturer itself if, for instance, the insurer thinks that a manufacturing fault was behind the incident.

However, the current AEV Act in the UK actually does not contain any specific provisions pertaining to user liability. The Law Commission has previously suggested that the legislation could be developed further in order to properly clarify the role of the ‘user-in-charge’.

US

While self-driving cars have already been trialed in the US, regulation differs from one state to another and some states do not have any laws or regulations for autonomous vehicles. California, for instance, has come up with a framework via a comprehensive approach. The state previously required back-up drivers to be present in all self-driving test vehicles but has now removed this requirement.

In Colorado, the Department of Transportation has partnered with Ford, Panasonic and Qualcomm with the aim of deploying Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything (C-V2X) technology which they believe with be particularly helpful in managing the heavily traveled Interstate 70 corridor.

Additionally, Florida passed a Bill in June 2019 which relaxed the state’s autonomous vehicle regulations. Under this new law, any autonomous vehicle would be permitted to operate within the state so long as it complies with the existing federal and state laws and has $1 million of liability insurance.

In reference to this, Tanenblatt stated, “The federal government’s going to have to step in and put some broad regulations in place, because you can’t have this patchwork of regulations when you’re dealing with something that crosses state lines.”

Echoing Tanenblatt’s statement, this is absolutely problematic. Many states and governors have passed and signed off laws and executive orders which, if it persists, will cause federal government to eventually interfere and impose “broad parameters”.

Australia

In Australia, each territory and state have their own road safety laws which, like the US, was bound to cause some major inconsistencies.

The National Transport Commission (NTC) launched the Australian Road Rules (ARRs) in an effort to unify these laws on a national level. The NTC has also disclosed that they plan to assess concerns related to autonomous vehicle integration, address them and change driving laws in general to support technology.

Singapore

For over two years now, the streets of the city-state have been home to self-driving vehicles. The government plans to even launch autonomous buses as it would be in line with Singapore’s sustainability aims.

There really is no established international standard when it comes to the regulation of autonomous vehicles. Since Singapore established the Center of Excellence for Testing & research of Autonomous Vehicles in 2017, it is safe to say that the city-state has spearheaded the testing, development and deployment of autonomous transport.

In 2017, the Ministry of transport introduced some Autonomous Vehicle Rules to be followed during trials. The Road Traffic Amendment recognized that motor vehicles did not need human drivers; this made Singapore the first country in the world to adopt autonomous driving on a wide scale.

At the time of the amendment Ng Chee Meng, the (then) Second Minister for Transport, spoke about the regulatory frameworks for autonomous vehicles and stated that “at the end of five years, the Ministry [of Transport] will consider enacting more permanent legislation or return to Parliament to further extend the period of the sandbox.”

“The Land Transport Authority (LTA) introduced a regulatory framework that minimizes the occurrence of accidents. Operators are required to have a qualified safety driver who will be able to take control of the vehicle in an emergency, hold third-party liability insurance and share data from the trials with the LTA,” said Satya Ramamurthy, Partner and Head of Government and Infrastructure at KPMG Singapore.

These are just a few examples of countries which have been at the forefront of adopting this technology widely. According to a KPMG study on autonomous vehicle readiness, the Netherlands and Norway also hold high positions in the index.

Risks and concerns are present in most technologies, especially new ones, because there is still so much we are not aware of. Therefore, areas of concern need further development and should be considered more often. In this case, members of the supply chain should synergize their efforts to proactively engage in policy development initiatives to ensure that the regulatory framework will have been developed with most potential concerns in mind. In this case, a regulatory framework should aim to balance the risks against the potential benefits of connected and autonomous vehicles. This is particularly important as we are shifting into a new era of transportation and the optimal regulation must be in place to ensure a safer and more efficient future.